Wrestlers’ Book Club #001: Dustin Rhodes - Cross Rhodes

Being somewhat of a closed shop and by nature shrouded in secrecy, few businesses do nepotism quite like professional wrestling. In the old days, especially, a familial connection could seem like the only way into the industry. Some second and third generation talents were pushed into the game by parents, others wound up there through something like fate. But your bloodline can be far more of a poisoned chalice than in other industries. The weight of expectation has put paid to greater or lesser degrees to the kids of Bruno Sammartino, Bill Watts, and Curt Hennig.

Dustin Rhodes is by no means an example of the form, but as his book details, it’s somewhat of a there but for the grace of God situation. Following in the wake of his father Dusty was no mean feat - the man was a sensation in his day, not to mention a shrewd power broker behind the scenes. As is often the case, Rhodes Sr. didn’t want his boy in the business, for reasons unknown to Dustin (he could’ve asked for the purposes of the book), but Jr. ended up in the ring anyhow. He warmly recounts his first night’s action, refereeing in Texas; per the author, his trousers split to such a degree that his penis and testicles were fully exposed, though he didn’t notice until it was pointed out to him by wrestler Tommy Young. Adrenaline being what it is, let’s give him the benefit of the doubt on that one.

Rhodes covers his wrestling career well, especially the early days. He speaks most fondly about the earliest stretch in Florida Championship Wrestling, working for peanuts and going out on the piss. As I’m sure will become par for the course with these books, he details some of the witless pranks the boys loved to play on each other (and like talking about after the fact even more). “Sometimes you woke up with really awful crap written all over your body with a permanent marker… Those ribs were really fun,” he recounts. What constitutes “awful crap” here doesn’t bear thinking about.

Dustin’s obvious love for the business comes across in spades. In perhaps the most in-depth passage in the entire book, he details his (hypothetical/composite) efforts to capture the interest of a disgruntled dad on chauffeur duties at a show. He also pays humble props to the previous generation who brought him up in the business like Arn Anderson and Bobby Eaton.

Nipping at Dustin’s heels, though, are his demons. It’s hard to imagine many industries are more prone to substance issues than wrestling, and Rhodes tumbles down the well trodden path of booze and pain pill addictions. He’s a little coy in isolating any particular inciting incident, but from his depiction of his relationship with his father, it’s fair to say the old man didn’t help altogether too much. Dustin’s eager not to drag his dad through the muck, as the two had since built bridges when the book was written, but even the stories he half-tells or details he drops don’t paint the American Dream in a good light at all.

The cracks in the relationship first come when Dustin meets Terri, who would later become his wife. Later, he receives a call from his father on the matter of his new partner, the only specifics of which he writes up being the charming phrase “do you know where she’s been?” The conversation, we’re told, “went downhill” from there. Barely a page later, Dustin stays at home with his ill wife and new baby rather than playing golf with his dad, and just like that, the pair don’t talk for five years.

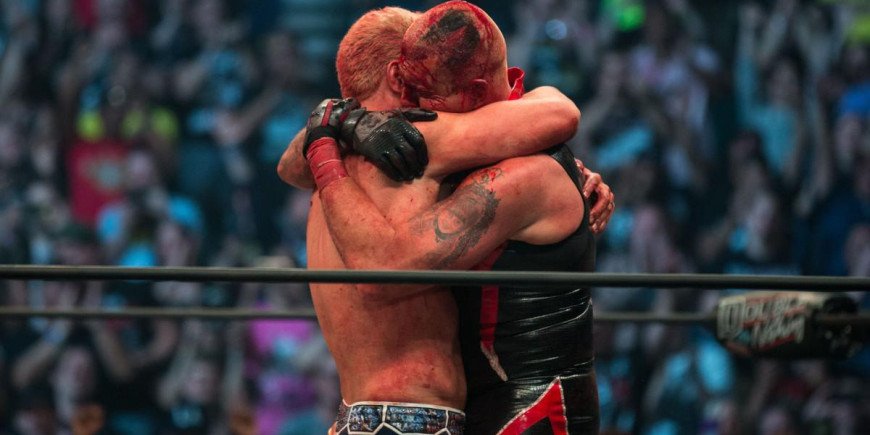

Reading between the lines, it’s impossible not to assume Rhodes has been extremely stingy with the story here. This is a WWE-released book, and Dusty would have been on the payroll at the time of its release (and possibly transitioning into his final, very well regarded role as an NXT trainer), so there may have been a desire to keep some of the saltier antics to a minimum, but it doesn’t make for a particularly interesting story when so much of the context is left out; it also robs the final tearful reunion of a bit of its power. Dusty’s perpetual absence is touched upon in part and Dustin acknowledges his desire to impress and emulate the old man, but he stops far short of suggesting that the bloke just wasn’t a very good dad.

The downward spiral that makes up the dramatic heft of the book is more a steady progression toward the bottom. In quick succession Rhodes details losing his job with WWE, working the indies, going back to WWE, and working the indies some more, all the while nurturing an increasingly expensive alcohol and pills habit. Again it’s all a little scant on detail, and again you could imagine WWE’s publishing arm nixing anything that felt too grim, or it may just be the case that Dustin wasn’t too keen on really luxuriating in that stuff. His eventual redemption arc is similarly low impact. There’s no great big moment of awakening; rather, he used the resources of WWE’s wellness programme to get the help he needed and finally went to rehab. Impressively, some 14 years after the book’s publication, he’s still wrestling at a high level.

While some of the darker details are passed over fairly quickly, Rhodes is commendably honest about his own shortcomings and fair (often more than fair) to those around him. His first ex-wife, Terri, in particular is given nothing but praise in the text, even as he describes her decision to deny him contact with his daughter at the height of his substance issues. There’s no bitterness at all; he concedes this was entirely necessary, even if it was painful. He doesn’t seem to have given a great deal of thought as to whether the sometimes questionable Goldust character was fueling homophobia in any way, but if there are murky waters around that gimmick, I don’t think it’s Rhodes’ fault. He does tend to come across well as a bloke and more specifically on LGBTQ+ issues (though I remember him tweeting something really weird about the homeless once), and this book does nothing to dent that image of him.

The slightness of the book does keep it from being a genuinely worthwhile bit of art, but the sense one gets is that this is as much to do with WWE’s censorious or otherwise cautious corporate office. It doesn’t feel like a ghostwritten affair and Rhodes describes the therapeutic effect of putting it together, so if it helped the chap come to realisations about his self-destructive tendencies and ultimately overcome them, it was worth publishing for that alone.